When meniscus or articular cartilage cannot be saved or repaired, a patient may be a candidate for restoration. This includes transplant and re-growth strategies.

Meniscal Restoration

Preserving meniscal function is a top priority for cartilage surgeons, but unfortunately, the great majority of meniscus tears cannot be repaired. When a large portion of the meniscus is removed, risks of arthritis increase greatly. For patients who have had the meniscus removed, the surgeon may offer an innovative solution called a meniscal transplant. Meniscal transplantation involves the use of a size-matched cadaver donor meniscus that is transplanted into the site of the original meniscus with the intent of regaining meniscal function. This procedure does not require patients to be on medications to prevent rejection. Intermediate term follow-up studies in the literature are encouraging, but transplanted menisci have a greater tendency to tear and re-operation rates are relatively high.

Articular Restoration

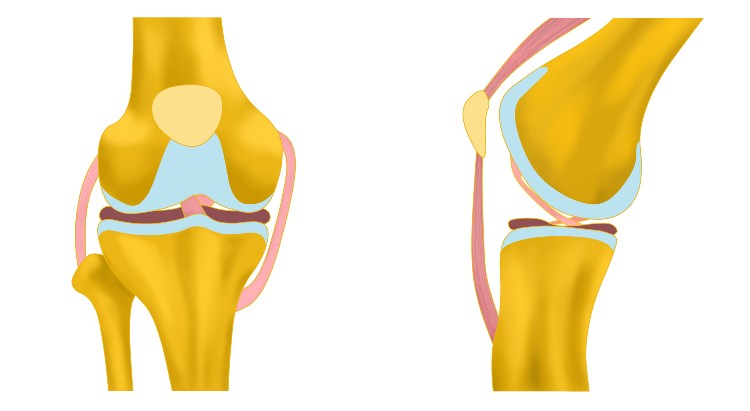

The articular cartilage that covers the bones at the joint experiences constant wear and tear. The cells of the articular cartilage, called the chondrocytes, produce and maintain the cartilage; unfortunately, chondrocytes do not replicate, cannot repair themselves when injured, and decrease in number as we age. Accordingly, damaged articular cartilage has very little ability to heal itself. Articular restoration procedures enable the surgeon to either stimulate a healing response or replace the worn tissue completely.

Microfracture

Microfracture can be used for small, well-defined cartilage defects. The defect must be meticulously prepared to create a smooth, well-defined “pothole,” after which holes are drilled or punched in the bone at the base of the defect. This allows the bone marrow and stem cells to bleed out, fill the defect and grow replacement tissue. Microfracture can be performed arthroscopically, but results in tissue that is more “scar-tissue”-like than normal cartilage, and has a greater tendency to break down over time. Accordingly, this technique is used only for very small defects.

Osteochondral Autograft (OATS)

This technique is analogous to a hair-plug transfer. The surgeon removes a small plug of the patient’s own cartilage along with the underlying bone. This is obtained from an area at the edge of the knee where it is relatively unimportant. This bone (osteo) and cartilage (chondral) graft is then transferred to the defect where a receiving hole has been prepared. In some cases, this procedure can be performed arthroscopically. The main limitation to OATS is that there is a limit to the amount of tissue available for “harvesting,” and the size of the defect treatable with this method is usually smaller than 3 cm (slightly larger than a nickel).

Osteochondral Allograft (OA) Transplant

Similar to the OATS procedure described above, this technique uses larger plugs taken from a cadaver knee rather than from the patient’s own knee. This provides much more available tissue, and allows filling of much larger defects. Although donor tissue is utilized, cartilage does not tend to incite any rejection reaction, and anti-rejection medications (such as are taken after a kidney or liver transplant) are not needed.

Autologous Cartilage Cell Implantation

Another strategy for larger articular cartilage defects uses the patient’s own cartilage cells, and is called MACI (Matrix-associated Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation). This is a two-step process, wherein the first stage involves an arthroscopic procedure to biopsy or harvest a small amount of the patient’s own articular cartilage. This tissue is then sent to a lab where the cells are cultured and increased from a few hundred thousand to over 10 million cells. These autologous (patient’s own) cultured cells are then impeded into a membrane which is implanted in the knee defect in a second surgical procedure. Over the course of 6-12 months, these cells will generate and grow new cartilage tissue to fill the defect.

Particulated Juvenile Cartilage

This technique also relies on the growth of new cartilage from cells, but in this case the cells are provided by small, minced pieces of juvenile allograft (donor) cartilage. These pieces are placed and secured into a cartilage defect using biologic glue. Only one surgery is required, rather than two as needed for MACI. However, results of this procedure are mixed, and tissue regrowth may be less predictable than some other options.

Cartilage Repair, Arthroscopically and Open Incision